Before it closes, I feel it incumbent to shore up my earlier poke at what Regina Hackett has called Seattle Art Museum's "Michelangelo debacle". To be concise, this show sucked. Why, is a longer tale.

Let's start at the beginning (of the gallery, that is; the ad campaign is another matter). Walking in, past the sculpture that opens the obviously more important, though curiously less advertised exhibition on the left, one is greeted at what would be the logical beginning of the show, if it had been laid out by a reasonable person, with a sign that reads "EXIT ONLY", and points visitors toward the entrance at the opposite end of a corridor lined with Calder. Presumably this was a conscious effort to funnel people into the Alexander Calder exhibition next door, but it makes for an awkward filtering. If we're honest with ourselves, it must be admitted that a good number of the people who are likely to visit a Michelangelo show will have absolutely no interest in modern, kinetic sculpture, so really this is just putting them out. Plus, if the exit and entrance had been reversed, people would have had to filter through Calder afterward anyway. So why the forced collision? The other result of this odd choice of layout is that when people do find themselves at the entrance to the galleries, they are met with signs of equal weight sporting the headings "MICHELANGELO WEDNESDAYS", "Emergency Exit Only", and "FIRE DEPT. VALVE". . . . Unfortunately it sets the right tone.

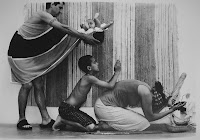

What follows inside the galleries is not so much an exhibition of Michelangelo drawings as it is an exercise in how to simultaneously over- and under-do a thing. Yes, there are drawings by Michelangelo on display. Eleven by my count — one of which is a grocery list — though the museum claims twelve. (Are they counting the letter to his nephew?) Also on display, however, is a lot of mediocre work by artists contemporary with, or merely looking back at Michelangelo. I am nonplussed. And then there are those awful things which the museum seems to be calling 'photomurals'. Photomurals? What they are are huge, gaudy pieces of vinyl stuck on the walls and used to distract from the exhibition's lack of content. Are we supposed to feel privileged to be looking at under-life-size reproductions of famous work shinily giving a hint of the wall texture to which they cling? Each drawing is also presented with a miniature photomural next to its wall label, showing where in the larger work this particular study fits. In other words, everything in this show is presented as important only insofar as it relates to something else which is important and not present. There are a few nice drawings on display — the best of which is the Study for Adam reproduced on the catalog cover — which could have and should have stood on their own, but when a My Favorite Things tour of a Renaissance exhibition by a PhD art history student includes a couple of giant stickers, one wonders if there isn't just a little bit of fluff.

Not to be left out, the writing is also crap. Did you know Michelangelo was "multi-talented"? Perhaps the most informative example is also the most absurd, and I'll share it with you in full. It's from the label of a little model by a "19th-century artisan", and reads like a children's book:

This model, showing how Michelangelo's David was transported to the Academia in the nineteenth century, prompts questions about Michelangelo's own use of technology: How did he move the original from his workshop near the cathedral to the front of the Palazzo Vecchio? (On a special sled placed over rolling logs.) How did he bring heavy marble out of the quarries? (By tying long ropes around the blocks and sliding them slowly down the mountain.) Did the ropes ever break? (Yes, killing and maiming workers.) How did he get the material up the Arno River from Pisa? (In barges loaded using wooden cranes.) How did the material finally arrive in Florence? (On ox carts.)Never mind that no marble by Michelangelo is actually on display here, nor even a study for a sculpture. Can't you just see the Way Things Work illustration?

Michelangelo was a great draftsman, and Seattle Art Museum promoted this show like they would showcase it, like it would be a revelation. "Michelangelo burned most of his drawings. See twelve that survived the fire." Unfortunately, flame retardance seems to have had little to do with quality in this case. And the rarity created by such a practice means it's hard for a museum like SAM to get its hands on the best work. Thomas Hoving, in 1993, declared the blockbuster show dead, saying it had simply become too expensive to gather up the kind of great work in quantities that made such events possible. The only way around this, I guess, would be to have a show so good that it would earn enough money to pay for those costs. That'd be excellent. Get people in the museum; get them telling their friends how great it is; get them looking at other artists; raise interest in art in general. But SAM didn't do that. Maybe the blockbuster is dead, and they know it. And until we know it, it seems a museum like SAM will be perfectly willing to lie to us to get us through the door.